Civil War.

In 1625 the west tower was built and a small bell installed.

The garrisoning of Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan troops in St Cybi’s is not the only connection. This 1899 statue of Cromwell outside the Palace of Westminster is by Hamo Thornycroft who carved the memorial in the church to William Owen Stanley. Photograph from Creative Commons, copyright Eluveitie.

The 1640’s witnessed the English Civil War, and St Cybi’s was directly affected.

A troop of Puritan soldiers was billeted in St Cybi’s church, which was closed for worship, but there is no record of the incumbent being ejected either by Parliament or at the Restoration. £53.13s.4d per month was paid to cover wages, fire and candles but not clothes, arms and equipment. Major Thomas Swift took command in 1650. He also became Postmaster and Churchwarden. His role as Postmaster would have been the only government post in town.

The troops were responsible for the removal of an old medieval font and many medieval tombs; destroying the statues from the canopied niches in the richly decorated porch, and they removed the holy water stoup from near the entrance door of the church. They also probably destroyed the ancient stained glass.

Apart from the damage they caused to the church the troops stabled their horses in the porch.

In 1658 Major Swift raised the height of the tower by 17 feet. The only logical explanation is to provide an improved lookout point, his ship had been captured by privateers. The coast was a dangerous place, not only from storms, but also from pirates. Major Swift claimed 12 or 13 ships from Chester and Liverpool had been attacked, including one near Holyhead itself. Given Cromwell’s attitude to the Irish Major Swift was also, no doubt, concerned about retaliatory action from across the Irish Sea.

Major Swift was a businessman and reputed to have owned the post barques or packet boats, which also provided passenger accommodation for government officials, troops and other travellers. If this is correct then he had a personal interest in protecting shipping from the pirates he was complaining about.

He probably bought land in the part of the town known as Swift Square, which is now the car park adjacent to the church.

The garrison was still in the town in 1661 and costing £900 a year.

We can assume the troops had left by 1662 as a new font was installed in the church this year. This font remains in regular use.

The damage to the tombs and other stonework has never been repaired. It is likely remnants of the damaged items were removed during subsequent restoration work, but there is no evidence of this.

The font, inscribed October 1662, Robert Lloyd. Robert ap H. V. Probert Wardens.

Today some of the church widows have stained glass, but the earliest of these windows is 1897.

In 1648 Rhys Gwynne, nephew and heir of the late Thomas Gwynne, fulfilled his uncle’s wish and granted the land and tithes of St Cybi’s, together with the curacies of Bodedern, Llandrygarn and Bodwrog, to Jesus College Oxford for the maintenance of two Fellows and as many scholars.

In addition to providing the livings for the Fellows, the gift brought in an average income of well over £100 a year from rent paid by lessees who farmed the tithes and later an additional direct income from rents of property which had developed in the town.

A copy of the draft Indentures of Agreement dated 1stDecember 1648 includes agreement by the College, in consideration of the property, to endow out of the rents, two Fellows of the College to be known as Doctor Gwynne’s Fellows and Scholars (with preference given to kindred of Dr Gwynne), £50. pa to the minister (appointed by the College) at the mother church of Holyhead, £5 pa to the poor of Holyhead, £40. pa to two ministers (appointed by the College) for the other churches or chapels and £5. pa to the poor of these parishes.

These tithes remained with the College until the disestablishment of the Welsh Church in 1920. In his ‘Antiquities of England and Wales’, published in 1786, Francis Grose wrote “This college [St Cybi’s collegiate church] was granted, 7 James I [that is 1610/11]., by that King to Francis Morris and Francis Phillips. It became afterwards the property of Rice Gwynn, Esquire, who, in 1648, bestowed it on Jesus College, Oxford, the great tithes for the maintenance of two fellows and as many scholars; and since that time the parish has been served by a curate nominated by the college. The living is a donative, not in charge, the certified value £35.”

Jesus College had been founded in 1571 for the education of future clergymen and came to be seen as the “Welsh college” because well into the 20thcentury the majority of undergraduates came from Wales.

Decay and Restoration

The extreme disrepair of the church in the late 17thand early 18thcenturies led to the insertion of a qualified repairing clause into some leases granted by the College, stating that the College was obliged to maintain the chancel and chapel of the church at its own expense.

On 4thJuly 1684 there is a report from Maurice Lewis to Walter Howell, the College Bursar, saying he had inspected the chancel and found the walls and roof in need of repair. The same document gives an insight to the problems of communication during this period. Maurice Lewis informs the Bursar he has been unable to find a drover with whom to send the rent and that it might not be paid until the London Fayre.

Reference to the lack of a drover refers to how cattle were then sent to market, and this would include cattle from the farms owned by the College. Cattle were bred on Anglesey for sale at markets in the south east of England, including London. Before the invention of the railways the only way to get them to market was to walk them all the way. The men who accompanied the cattle and were responsible for them during the journey were called drovers. Sending large sums of money over any distance was then a very risky business. Sending the cash with the drovers was considered one of the safest methods.

In 1711 the incumbent, Simon Langford, complained that the chancel was a tottering wall ready to fall and the roof was rotten, needing new timber. Related to this is a memorandum endorsed on a lease of 1710 between the College and Maurice Owen of Holyhead, by which it is agreed Maurice Owen will be allowed the money he paid for Queen’s tax and that the College will put the chancel in good repair, after which it will be maintained by Maurice Owen. In 1713 it was reconstructed. The Rood Screen and a small access tower were demolished.

During this work the stone coffin of Prince Rhodri, buried before the High Altar in 1195, was discovered.

Time to take a seat

Originally seating in church was limited to benches along the north and south walls in the aisles, meant for the aged and infirm – hence the saying ‘To go to the wall’.

Following the Reformation, and the rise of the sermon as central to the service, the pew became a standard item of church furniture. In some churches, pews were installed at the expense of the congregants, and were their personal property; there was no general public seating in the church itself. In these churches, pew deeds recorded title to the pews, and were used to convey them. Pews were originally purchased from the church by their owners under this system, and the purchase price of the pews went to the costs of building the church. When the pews were privately owned, their owners sometimes enclosed them in lockablepew boxes, and the ownership of pews was sometimes controversial.

The present pews are Victorian, but the plaques on the two pews at the front of the photograph read “Penrhos” indicating as late as the 20th century space was reserved for the servants of the Penrhos Estate. In addition, the Stanley family, who owned the Penrhos Estate, had its own pew in the south transept.

Lucy Williams gives an account of such a dispute which occurred in St Cybi’s in 1733. She writes “William Owen, the young owner of Penrhos, had died leaving the estate involved by the costs of building the new mansion and a large jointure to his widow [a jointure is an estate or property settled on a woman in consideration of marriage, to be owned by her after her husband’s death]. His mother had only three of her twelve children remaining and their health was a continual anxiety. Her pew in St Cybi’s adjoined that of Mrs. Welch, of Swift’s Court, for whom Madam Owen had a great liking and respect, when suddenly Thomas William Thomas took possession one Sunday of this seat where Mrs. Langford (the curate’s wife) used to sit. It was thought by everybody that those “sorry scrubs” Lewis Morris, Wm. Vickers and Griffiths the Collector had put Thomas ap William Thomas to the manoeuvre as a preliminary to annexing seats for themselves, and that “Lewis Morris had a mind to be a Sir Robert (Walpole) at Holyhead with W. Vickers as next man and Griffiths the Collector as prime Councillor to them both.” Thomas continued the assault on successive Sundays climbing over into the pew in the face of the congregation and picking the padlock that Madam Owen had placed on it. Madam Owen begged her son Edward not to be worried about her being insulted by these scrubs, that she would deal with them and keep them out of her seat, “which sorely vexes them”! The gallant lady did, and Richard Thomas was censured and condemned to pay the costs of the suit by the Proctor of the Diocese.”[i]

Church repairs and Civic responsibilities.

St Cybi’s has church records going back to 1737, including details of the Churchwarden’s accounts. From as early as 1555 Parishes became involved in the upkeep of the highway. Over time and through various Acts of Parliament the Parish acquired various powers and responsibilities which were administered through the Vestry, that is the governing body of the Parish.

Extracts from the church records between 1737 and 1828 are set out in the section headed Churchwarden’s Accounts. These include items relating to Church affairs; Church maintenance; Welfare; Road and general maintenance; local policing and administration of Justice.

We can see from these accounts that considerable work was done in 1739 re-roofing the tower (referred to as the Stipple in the accounts) with 2500 slates purchased in 1738.

In 1743 there is reference to the cost of delivering lead by sea. It is not clear if this was for the church or for Eglwys y Bedd.

Eglwys y Bedd, in the south west corner of the churchyard, the location of Thomas Ellis’s free school. The building, which dates back to the 14th century was previously a chapel. What remains of the original building would have been the Nave of the chapel.

In 1743 with support from his friend Edward Wynne, Chancellor of the Diocese of Hereford, and the Chancellor’s sister Anne Owen of Penrhos, Thomas Ellis, Perpetual Curate of St Cybi’s, started work on the first free school for the children of Holyhead, which was opened in 1748. The school was situated in Eglwys y Bedd, which he had restored for the purpose. At the time of the school’s establishment he wrote of his “real concern for ye swarm of children, wch grow in a manner wild for want of schooling”.

Initially the school was financed by Chancellor Wynne, who by a bond of 25thNovember 1748 end

owed it with a capital of £120; “the interest whereof is to be paid annually on the 24thNovember to a schoolmaster, who is to teach six poor boys of the town to read and write”.

Thomas Ellis was a Fellow of Jesus College, Oxford. He was a BA and a BD. He was appointed as a Perpetual Curate at St Cybi’s in 1737. A Perpetual Curate was a class of resident parish priest who was supported by a cash stipend and had no ancient right to income from tithe or glebe.

Thomas’s outlook on religion meant that he did not approve of some of the local customs, which, he thught, were used as an excuse for merrymaking. Thomas moved the patronal festivals to a weekday. In a 1754 letter his friend William wrote saying he was expecting his father to visit “for our patronal festival, which Mr Ellis moved from Sundays. There were three Sundays in the month of July when there were shown, and probably carried around the relics of St Cybi, and from then until now they were known as Relic Sundays. The whole country used to come here to celebrate the feast, i.e. to eat, drink, get drunk, to fight and swear and curse”.

Thomas introduced a programme of games including foot and horse races in order to improve conduct.

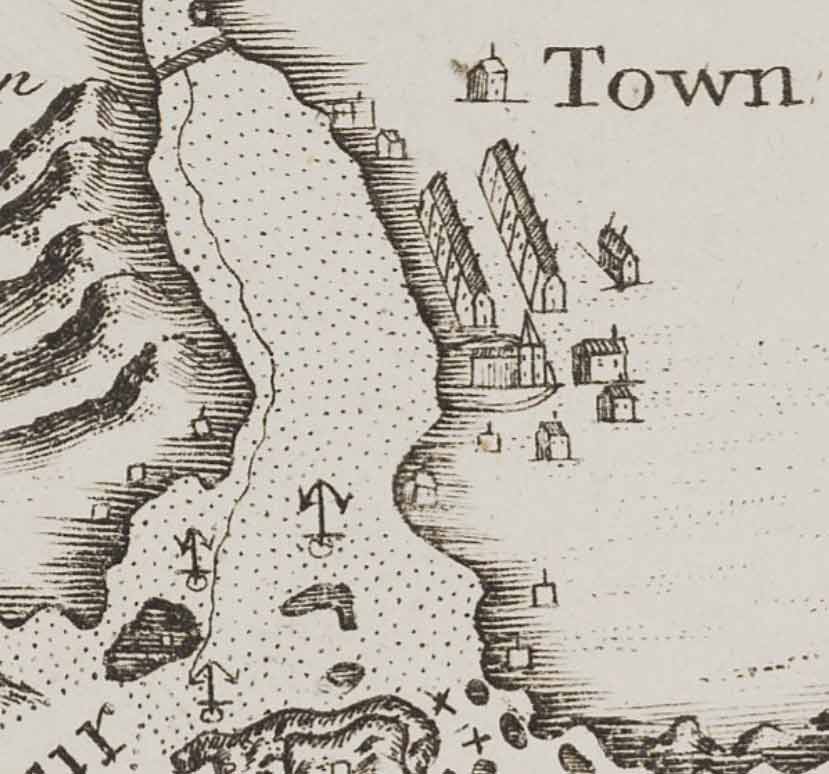

Detail from William Morris’s 1748 plan of Holyhead Bay and Harbour Courtesy National Library of Wales

One of Thomas Ellis’s great friends was William Morris, one of the four Morris brothers, Lewis, Richard, William and John –’Morrisiaid Môn’ (the Morrises of Anglesey). William was Choirmaster and Warden at St Cybi’s. One of Lewis Morris’s many talents was as a cartographer. On behalf of the Admiralty he prepared various plans of the Welsh Coast. This detail from his plan of Holyhead Bay and Harbour. shows (courtesy National Library of Wales) Holyhead town as consisting of the church, one street and a few scattered houses. The plan is dated September 1748. It predates any improvements to the harbour and shows what is now the harbour as no more than the mouth of the river, which is dry at low tide.

[i]The Development of Holyhead: Transactions of the Anglesey Antiquarian Society, 1950.